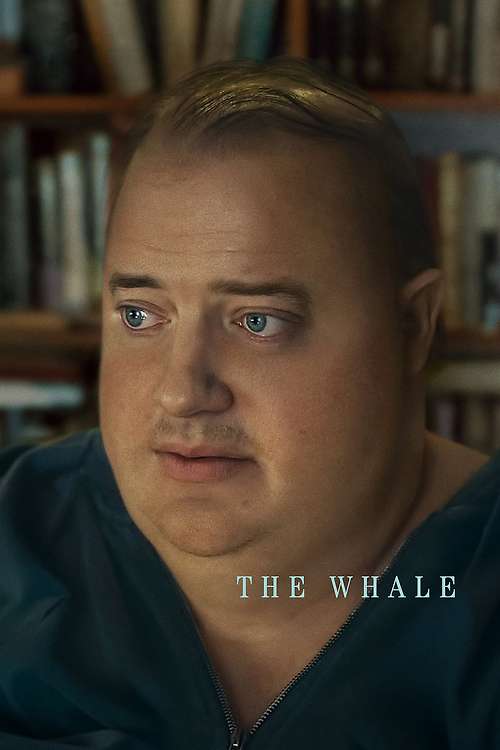

In THE FOUNTAIN, Thomas has found eternity, while in mother!, Him seeks it through art, a means itself to transfinitude; and now, in THE WHALE, Aronofsky is eschewing eternity altogether. Instead, it’s transfixed on life’s finitude; Charlie is dead set on making meaning in the immediate. Despite Protestant Christianity being a plot point, there are more subtle religious parallels we see with Charlie devotedly seeking forgiveness from his estranged daughter. Making amends before death, despite it being common fodder for storytelling, has its origins in the forgiveness we must beg God for before we come to the end of our sinful existence. When we use the amends-before-the-end-of-life framework for a story but we elide the forgiveness required from God, it underscores the point that Aronofsky misses altogether in THE FOUNTAIN, and more importantly a point missed by religions which promise eternal life: the fact that life has a fixed beginning and end, that our time to be conscious here on Earth is limited, is what gives us purpose. To make amends at the end of life is, flat out, the opposite of the lesson, despite it being precisely the one taught to us in Bible school. To wait until there’s no time left is to deny oneself, or those others that we may have wronged, the amends they’re owed now; the longer we wait, the more we subtract from our purpose, our calling, or if you’ll allow me it, from our ability to self-actualize. Charlie waited too long, so his plot for redemption was doomed from the beginning.