In This Life, philosopher Martin Hagglund makes the argument that the very fact that the time we have to be conscious here on Earth is limited is what gives life value, what gives it meaning. If we have infinite time, then nothing matters. In The Lathe of Heaven, Le Guin expands on this existential dialectic to explore not infinite time, but infinite opportunity. When a man is given infinite opportunity, it has the same effect—he can erase pain, but pleasure dies with it as well. The meaning we make from life is the synthesis of these opposites.

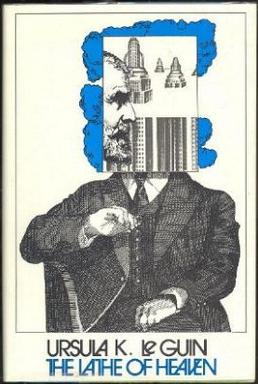

The Lathe of Heaven is the story of a man, George Orr, who has been blessed with the curse of effectual dreaming. When he dreams, reality shifts. Under governmental mandate, Orr must see a therapist after being caught borrowing a neighbor’s scrip card—he’s exceeded his ration of anti-onierics—drugs he takes because he fears dreaming, a transitive fear borne from the terror of the responsibility that manifesting reality entails. His therapist, William Haber, does not share this fear. Instead, he is morally, despotically, compelled to put Orr’s gift-curse to work to “fix” reality. Racism, hunger, overpopulation, malevolent extraterrestrials, all erased. Haber, a man, acts as God to flatten life’s curves. The book’s title itself acts as a warning to men like Haber, but also as a presentiment to the reader—a misquote from the writings of Chuang Tzu:

To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.

Haber is unable to stop at what cannot be understood, and exercises the infinite opportunity given to him through Orr. He doesn’t just leave meaning behind as a casualty, but instead the very fabric of reality itself. Le Guin takes to making this dialectic literal, and Orr must race against the erasure of being and stop the encroaching nothingness.